Black.

In grade school in the 1940s black was just a color in a box of

Crayola Crayons. A sad color because people wore black to

funerals.

In high school, black became a fashionable color. Wearing

a black dress meant you were sophisticated.

By the time Givenchy designed Audrey Hepburn’s black

dress in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, my closet was almost all black.

When I think of black today, I don’t think of clothes. I think

about how little I knew or thought about being Black in

America.

When I was young we called dark-skinned people “colored.”

In elementary school there was only one colored girl in my

class, Carolyn. She hardly ever spoke. Neither did I. I was tall

and gawky and nobody paid attention to me or Carolyn.

Carolyn and I never raised our hands to answer a question.

We hid in the bathroom when we had a spelling bee. If our

classmates were choosing teams, Carolyn and I were always

chosen last. And we were never invited to Arianne Ruskin’s

fancy Park Avenue birthday parties. I was glad Carolyn was

in my class.

But Carolyn and I never played together after school. We

weren’t that kind of friends. I lived on 66th street East of

3rd Avenue—Irish bars and railroad flat apartments.

Carolyn lived above 100th Street—white people didn’t go

there.

I don’t remember any colored girls attending my all-girls

college in Boston.

Then colored people were called Negroes.

I got married and moved to North Stamford, Connecticut.

All my neighbors looked like me.

I moved to Livingston, New Jersey, when I had children.

My neighbors there all looked like me. I was busy with my

kids and with unimportant stuff that seemed important to

me at the time.

At every job I’ve ever had, my coworkers looked like me.

Even in the movies all the big stars looked like me except

for Lena Horne. She was beautiful and had beautiful

clothes. She could sing, too.

Then Negroes were called African-Americans.

I remember being in the shoe department of Macy’s one

day. A saleswoman about my age was waiting on me. When

she went in the back to get me a 9 ½ narrow, a salesman

asked me who was waiting on me. I didn’t know what to say.

I didn’t know my saleswoman’s name. Should I say

“the African-American woman”?

I was born in New York but my ancestors came from Europe.

If someone called me a European-American, that would have

felt weird. I’ll always remember how uncomfortable I was

that afternoon because I didn’t know what name to call the

saleswoman.

Shakespeare said, “What’s in a name? A rose by any other

name would smell as sweet.” He was wrong. Names can

make you feel bad or good.

I never liked my name. I was named Ilene when I was born.

But I came out with red hair so my family always called me

Ginger, and then Gingy. But in school I was Ilene, very shy

and scared. Even today when someone calls me Ilene, I still

remember those feelings. But when someone calls me

Gingy, I feel safe.

My older sister was born in the Flower Hospital in New York

and my mother named her Blossom. She got the nickname

Tootsie. Everybody, except her teachers, called her Tootsie.

When she got a boyfriend he didn’t like either name so he

renamed her Bonnie and that’s what everybody called her

the rest of her life. Except me. To me, my sister was always

Tootsie–not Bonnie.

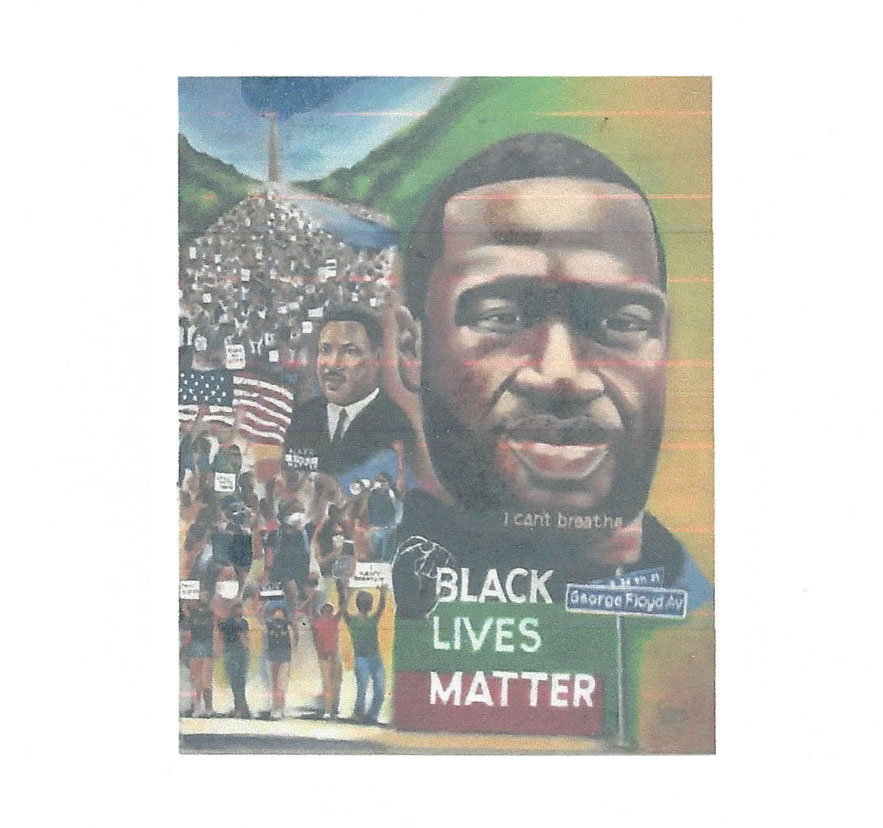

When Black took the place of African-Americans and “Black

Lives Matter” became the phrase that woke up the world,

it woke me up, too. I hadn’t spent much time thinking about

people who didn’t look like me or touch my life.

Of course Black lives matter, Blue lives matter—all lives matter.

But I saw things happening to Black people on TV that would

never happen to me just because I happen to be white.

If everything in my life and your life stayed the same,

except we were Black and our families were Black, nothing

in our lives would be the same.

You’re just a button click away and I’d love to hear from you.

About your world,

your family, your joys and frustrations, growing up, growing older, even recipes– even though I stopped cooking–by request–years ago.

Goodbye until next time…

Hope your day turns out as well as I hope (but doubt) mine will,

Gingy (Ilene)

Gingy,

Wonderful!!! So well thought out and well developed.

Thank you again.

Love, Nancy

Hi Gingy (i don’t ever want you to feel unsafe). I had similar feelings about my name, but I’ll save that story. I think most people who aren’t a person of color are never able truly understands what all the fuss is about when those who are say they are always aware of their skin color. Even those of us who claim that color doesn’t matter to us, and think we’re being generous and unbiased by saying that, don’t realize that to a person of color it is almost as offensive as judging them by their color. Color is ALWAYS present in their lives. The thing is, to say skin color doesn’t matter is like saying we are all exactly the same. Yes, on some levels we are, but our cultures and traditions, our accents, many of the things that define our differentness, are important to each individual. We are each unique even if our innards are identical. We don’t want to be liked DESPITE who we are/what we look like…we want to be appreciated BECAUSE of who we are, our color, our backgrounds, all of it….and certainly not because the the person doing the appreciating is proud to be politically correct. To say color doesn’t matter is be very aware of color and to defiantly “ignore the elephant in the room”. We CAN’T ever really know. I don’t think there is anything wrong with saying “that lovely black (or African American) saleswoman is waiting on me.” Because to be afraid to use that legitimate descriptive makes us feel un-PC, we who obviously think it woud be insulting to be described as who you actually are…as if a person of color wouldn’t be proud of who they are. Unless a person’s color is used in a judgemental or derogatory way, it is merely a descriptor….it’s be great if one could also remember the color of her dress.

Such an honest and thought provoking article.

You hit the nail on the head.

I grew up in Belleville, New Jersey and I am Jewish. I was never invited to any classmate’s’ birthday party nor did I ever get a Valentine’s Day card from any of my classmates. I had teachers who humiliated me in from of the class because I did not attend school on any of the Jewish High Holidays. I could go on with a long list of what it is like being an outsider, but I rose above it by excelling in education and having a strong family life. I never saw myself as a victim nor did I ever resort to violence and looting. Yes, all lives matter, but it is up to the individual who decides to do with his or her life.

this should be a letter to every newspaper

Right on. As always.

Powerful. This post speaks volumes. I wish every person would read this. This is real and so beautifully and eloquently said. Thank you for this post. As always, I look forward to your next one. You are a one of a kind, extraordinary person. Much Love and appreciation for you Ilene!

I grew up in Queens and my experience was not the same as yours. There were no “coloreds” in my school. My parents were kind, not racist even though we had a “colored maid” living in our house. We thought we were giving her an opportunity to rise above. We thought being nice to her was all we had to do. We had no idea about what we now call institutional racism which makes me feel stupid . I hope things are really changing now. Thanks Gingy for making me think about my carefree childhood. I do enjoy your musings. Keep it up.

I do remember one African American girl in our class at Simmons. Joann Porter, now why do I remember her name?! She must have felt very much alone. We smiled at each other and once, walked to class together. That’s all I remember about her. So with all the turmoil in our country, we have made progress in race relations, painfully slowly!

Thank you Gingy, a wonderful piece as usual. My sister Phyllis went to that girls college with you and you once spent a weekend at our home. Your experience parallels mine to a great degree. The recent events promoting Black Lives Matter and conversations with my granddaughters have brought me a new understanding-long overdue. I’m glad we still are learning as we live, and we’re not too old to understand new and better points of view.

Hi Gingi!. I read all your books and saw the play and was thrilled to interview you myself. Thanks fir everything! Sally

I always love what you write! I wish you would write more often!

Dear Ilene, Bravo! What a great piece! I so enjoy reading every blog posting of yours that arrives in my email box. I am sorry I have never responded before…and shame on me! Especially since there are times I read about your life and it’s like you’re writing about me. Just wanted to tell you how much I enjoy your words. They’re so appreciated! Thank you, G.

Ilene,

Another gem! So ‘you.’ Thank you for sharing it.

Love, Nancy

Great blog! I grew up in integrated neighborhoods, and always loved black people but, like you, didn’t see them after school. Was taught about slavery in school as a kind of extended family, all working together at the plantation. I was in my thirties when I first saw how military, how horrible, how much policing and torture were required to make it work. Racism is so normalized, has been for so long! What is skin color? it’s just a slight gradation, magnified as a point to enable slave holders. The whole thing is just so awful. I can’t believe black people don’t just go crazy or have a revolution. Thanks for this wonderful piece. XX

Hi Ilene,

Love your blog as usual.

K.